Podcast Episode 92: Deep Dive on Conscientious Objectors in the Civil War with Jonathan Stayer

Curious about conscientious objection during the Civil War? Jonathan Stayer returns to discuss his favorite subject and its deep roots in Pennsylvania's history.

Jonathan Stayer joins us once again on the podcast, marking his third appearance. This time, the topic is especially close to his heart—conscientious objection during the Civil War, particularly in Pennsylvania. While previous episodes covered the South Central Pennsylvania Genealogical Society and Camp Security, this discussion dives into a subject Jonathan is passionate about. If you're interested in genealogy and historical nuances, you’re in for a treat.

Watch the full interview:

What is Conscientious Objection?

Definition and Historical Context

Conscientious objection during the Civil War was often referred to as "conscientious scruples". This term described people who, primarily for religious reasons, opposed military service.

Three main groups constituted the historic peace churches:

- Mennonites: Including various sub-groups and often lumped together with the Amish.

- Quakers: Known formally as the Society of Friends.

- Brethren: Referred to as the German Baptist Brethren during the Civil War, which included various sub-groups like the Dunkers.

These groups maintained that taking up arms against anyone, including enemies, contradicted the teachings of Jesus in the New Testament.

The Geography and Demographics of Conscientious Objection

Key Counties in Pennsylvania

Conscientious objectors were not uniformly spread across the state. As Jonathan points out:

"The largest number came from Lancaster County, and the second largest number was from either Bucks County or Montgomery County."

These areas had strong populations of Mennonites, Quakers, and Brethren, reflecting their collective stand against military service.

Unique Stories and Local Differences

Local attitudes and administrative processes varied significantly. For instance, Lancaster County was a hub for the Amish and Mennonites, whereas Bucks County had a stronger Quaker presence.

"Everything is very local, and you have to study the history of the area to know exactly what you're dealing with."

The Draft and Conscientious Objection

The 1862 State Draft

In 1862, Pennsylvania’s constitution allowed those with conscientious scruples to claim exemption upon payment of a commutation fee. Although the state legislature never settled on this fee's amount due to various disputes, the federal government took over the draft process in 1863, thereby simplifying this exemption's requirements.

The Conscription Act of 1863

The 1863 Conscription Act lacked direct exemptions for conscientious objectors. However, objectors could:

- Pay a commutation fee or

- Provide a substitute.

Most peace church members saw providing a substitute as morally equivalent to serving, leading many to opt for the commutation fee despite their reservations.

Documentation and Records

Categories of Draft Records

Several categories of records help genealogists track conscientious objectors:

- Enrollment Lists: Created before the draft, listing eligible men.

- Medical Registers: Examining physical fitness for service.

- Descriptive Registers: Detailed personal information about draftees.

Key Locations for Records

- National Archives in Philadelphia: Holds records for the federal draft.

- Pennsylvania State Archives: Holds state draft records.

- County Historical Societies: Often hold enrollment books and other detailed records.

Research Tips for Finding Conscientious Objectors

Identifying Potential Ancestors

When considering if an ancestor was a conscientious objector, check for the following clues:

- Age: Must be between 18-45 years old during the Civil War.

- Gender: Only males were subject to the draft.

- Church Affiliation: Membership in peace churches is a significant indicator.

Dive Into Archival Research

Jonathan provides several detailed steps to follow:

- Start with County Records: Enrollment books and local history books.

- Move to State Archives: Pennsylvania State Archives for broader records.

- National Archives for Federal Draft: Especially useful for detailed medical and descriptive registers.

Useful Resources for Research

Jonathan mentions several key resources:

- "Mennonites, Amish, and the American Civil War" by James Lehman and Steven Nolt: Best for understanding the impact on peace churches.

- "Conscientious Objectors in the Civil War" by Edward Needles Wright: Focuses more on Quakers.

- "We Need Men" by James Geary: A comprehensive look at the draft in the North.

- "One Million Men" by Eugene Murdoch: Explains the draft mechanism in detail.

Conclusion

Conscientious objection during the Civil War remains an underexplored topic in American history. Jonathan Stayer's lifelong quest to document this aspect provides invaluable insights for genealogists and historians alike. Whether through detailed archival research or individual family histories, uncovering the stories of conscientious objectors adds a rich layer to our understanding of the past.

"It’s an unexamined part of the Civil War. That time period is way more complicated than we ever give it credit for."

Your Pennsylvania Ancestors is distributed through the following channels:

Learn all about the history and details of the Your Pennsylvania Ancestors podcast.

Transcript:

Well, Jonathan Stayer is back for a third time on the podcast. The third time is the charm because we're going to talk about Jonathan's favorite topic today. So this is even better. Not that he didn't enjoy talking about the last topics that he talked to us about. Check out those episodes on the south Central Pennsylvania Genealogical Society, which he is the president of, and also camp security, which he is on the board of if you want to catch up with all of Jonathan's episodes.

But in this one, he's going to talk about his favorite topic, which is conscientious objection. In the history of Pennsylvania and in particular the civil war. Jonathan, welcome back to the podcast. I'm thrilled to have you back talking about this because this is a topic I'm interested in, too. Thank you, Denyse.

All right, so what got you interested in conscientious objection? Let's start there, I think, and then give us. And then give us a definition of what that is for those of us that don't know what conscientious scruples are, which was often seen in the paperwork of the time. Well, I actually have a very personal connection to this topic. When I was in college, an undergraduate, I started becoming interested in my family history, and I started researching my family and came to learn that most of my ancestry comes out of what we call the historic peace churches, particularly the church of the brothren.

And I also have mennonite amish ancestry. And when I started working at the state archives, Pennsylvania State Archives in 1985, I discovered this file of civil war conscientious subject or depositions. And I knew that my star ancestors were brethren at the time. And I thought, I'm just going to look in here and see if, well, sure enough, there was the deposition of my third great grandfather, Adam Stair, and of all his brothers, David, John, and Daniel. And so I thought, well, this is very interesting.

I'd like to know more about this. And I started doing research and found that had very little had t been written about it, and very few people knew what resources to go look for to find more information. And so it started basically. Well, I say lifelong was my adult life quest to uncover everything I could find about Pennsylvania's civil war conscientious objectors. Because all of my ancestors at the time of the civil war lived in Pennsylvania.

And I should mention throughout this podcast that when I'm talking about consciousious subjectors, generally talking only about the experiences in Pennsylvania, I always tell people experiences varied from state to state, and even in Pennsylvania, they vary from county to county. So you can't take what I say and apply it to Maryland or Ohio or New Jersey or anyace else. And in some cases, the things I tell you may not even be true in certain counties in Pennsylvania. So it's a very personal thing, very local thing, and you have to study the history of the area to know exactly what you're dealing with. And that's how I became interested in documenting Pennsylvania civil war.

Conscientious subjectors. Now, the term at the time of the civil war was called conscientious scruples, because people had scruples against serving in the military. And this was primarily for religious reasons. And again, it was primarily for the churches. We call the historic peace churches.

And they fall into three general categories. You have, the most numerous are probably the Mennonites. So you have the Mennonites, the various Mennonite groups. And with those, I would lump the Amish. And I will say that during a civil war, sometimes when you see the word mennonite, they're also referring to Amish, or sometimes when they're referring to Amish, they might be including Mennonites, because some of the people weren't clear on the differences between the groups.

So the first main historic peace group thread would be the Mennonites. The second one would be the friends or Quakers Society of friends. And the third mainstream of historic peace churches would be what I call the Brethren. Now, at the time of the civil war, they primarily known as the German Baptist Brethren, which is now represented mostly by the church of the Brethren. Although there are other Brethren groups today, the Covenant Brethren, Grace Brethren, Dunkardren Brethren Church, all grew out of that group that was known as a German Baptist brethren.

In addition, during the civil wartime, they frequently recalled dunkers or Dunkards because they believed in adult baptism by immersion, completely dunking the person in the creek. Those are the three streams of historic peace churches. And those churches believed that it was wrong to participate in the military because of the teachings of Jesus, and particularly in the Bible in the New Testament. So when Jesus said to love your enemies, they took that literally, meaning that you should not take up arms against your enemies. And they cite other verses as well to support that.

And it's a traditional. Well, at least for the menites and the Brethren, it's a traditional anabaptist belief that you do not participate in the military. Amazing. So this is a lot of people, I mean, because there's a lot of people of these faiths across, I would say, most of south central Pennsylvania, into up along the Schukill river, too, into Beks County, Lehigh County, Northampton county, and then, yeah, down across Lancaster. Of course, today everyone thinks of the Amish in Lancaster and the Mennonites.

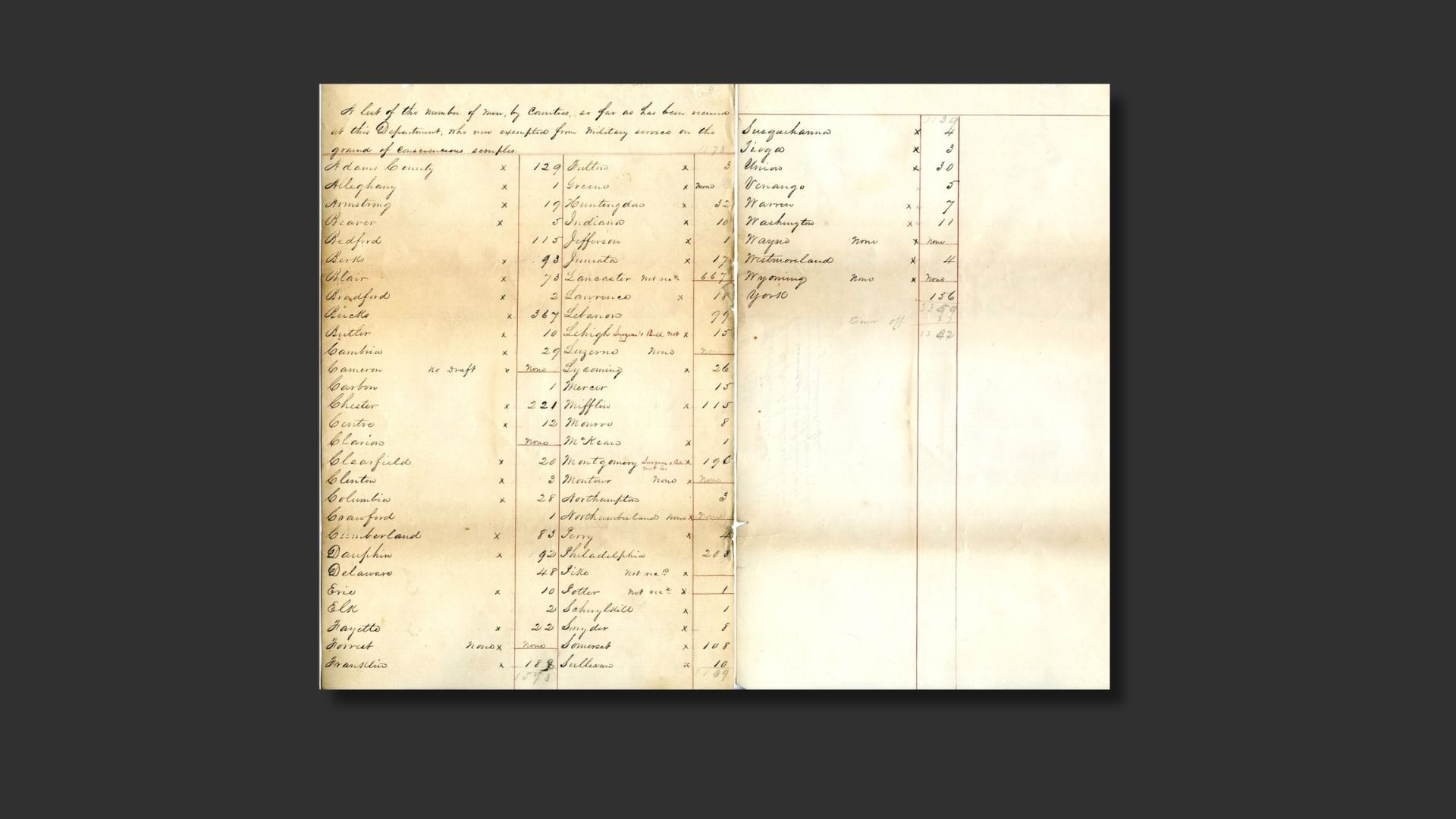

York, Adams. Am I getting all the counties right. Or again, dealing only with Pennsylvania? And I provided you with that copy of that document that shows the counties in 1862 and the objectors from each county. I think the largest number came from Lancaster county, and the second largest number was from either Bucks county or Montgomery County.

O Lancaster county would be the center of particularly the Amish, the Mennonites. Well, practically all the Quakers were not as numerous in Lancaster county. Where elsewhere. But the other Peacece churches were well represented. Lancaster county and Montgomery county.

Again, you have Mennonites and Brethren. And Bucks county, of course, is heavily Quaker friends. I apologize to my Quaker friends, but I'm going to use Quaker instead of friends, because that's what I'm common used to doing. But they're formerly known as a society of friends. There were large numbers of Brethren and some Mennonites out in Franklin County, Bedford and Somerset counties, Fayette County, Indiana county in Pennsylvania.

Mostly the southern tier counties is where you find the concentration, although there were some objectors scattered throughout, elsewhere in the state. But it's primarily the southern part of Pennsylvania where you find the objectors coming from. And I want to mention something. In 1862, we know that Pennsylvania had around 3400 conscientious objectors. That's more than any other state, north or south.

And I haven. I don't have the documentation for this, but I tell people it's probably more than all the states, north and south together, combined. Because the other states did not have as many conscientious objectors as penal. Pennsylvania did. And a lot of these churches had their centers, had their population centers and their administrative centers in Pennsylvania.

Now, there were numbers down. If you go down the Shenandoah Valley, you have brethren and Mennonites down there. And I think what their neighborhood of 300 to 400 may be conscientious subjectors in the Shenando Valley, Virginia area. And you had some in Ohio and going further west. But of course, the concentration of these groups was in Pennsylvania at the time.

Okay. All right. Thank you for clarifying that. So, you know, people listening, you know, listen closely to your counties where. And because I know the.

Knowing the religion of your ancestors can sometimes be tricky to figure out. If it wasn't handed down to you or through your family, you knew you had men of military age during the civil war who did not serve, and you knew they didn't serve. And you suspected that they were conscientious objectors. And then you look for the proo in the 1862 depositions. Well, actually, I didn't suspect they were.

I just. Oh, you knew? No, I didn't know. I knew. I wasn't sure what any of them had done, and I just knew it because they were brethren.

They probably did not serve. And then when I found the documentation that they did not serve, that verified that. Ok. Yeah, okay. So you were.

This was all completely new to you, the time, and just like many people listening, this is gonna be completely new. So give us the timeline then, of 1862. In 1862, the federal government says to the states, you need to send us more men, and puts the states in charge of doing a draft, essentially. Or would you call it a draft? Or is it more like a.

Well, the way the legislation read is they were supposed to call. The states were supposed to provide men from their militious systems, and each state was given a quota. If they could not meet their quota, they were then authorized to conduct a draft. Okay. And the exact way that worked out escaped me.

At the moment, however, the draft in Pennsylvan, the enrollment occurred. So in other words, the listing of the names who would be eligible for the draft occurred in August, generally August or early September of 1862. And in Pennsylvania, the actual drafting of individuals occurred in October of 1862. Okay. There was confusion because the federal legislation said that the age for drafting would be 18 to 45.

However, the militia laws in place in Pennsylvia time said militia service. The minimum age for militia service was 21. So sometimes when you look at the records, and this is why I say it varies from county to county. In some counties, they actually listed the names of individuals who as young as 18. Other counties, they started with 21.

Or you'll see some places where they listened to people who were 18. Then they struck them off as being too young for the draft. And I'm sure there was confusion. Quite honestly, when I studied the draft records, you wonder how the draft ever succeeded, because there'so many questions, so many problems. There was a very good book written called we need men by James Geary, and he points out some of the problems.

Now, he primarily deals with the federal draft, but he points out some of the problems they had with implementing the draft and the misunderstandings that occurred over time. Ye, the federal draft was in 1860. Threect occurred almost the same time of year. The next summer is when that. Well, I guess the legislation passed in March, but then they started to actually send federal marshals out or draft board people in April.

Okay, so back to 1862. So when did people have the capability to file these objections to military service? Was it after the draft had started, or was it before? Most people don't know this, but Pennsylvania's constitution, which was in place of time, was the constitution of 1838. And there was an article in the constitution that provided for the exemption of those having conscientious scruples upon a payment of a commutation fee.

And so when they established the procedures for the 1862 draft in Pennsylvania, eventually they provided that individuals could file what was called a, what we now call a deposition. It's basically a form saying that they were opposed to military service and they were claiming this section of the constitution. Those generally were filed prior to the draft in October. So I think Adam stairs was filed in September, I believe, around, say, September 16. I'm not sure.

Somewhere around that time period. And I think most of the ones I've seen were filed before the draft actually occurred because they wanted to know that these men were not going to be eligible. That was a direct exemption from the draft, which was different. And we'll talk about this a little later on, probably, but the federal draft laws had no direct exemption for objectors. Pennsylvania did, however, because the constitution did not set the fee that was to be paid.

That issue came before the state legislature. I think it started in January. Certainly by February of 1863, they took up the question, how much should these men be paying for to escape the draft? Right. Well, I think it was the House batted around, and the discussion in the House is very fascinating.

One man said, one representative said, $1,000 is not enough for a man life. And other representatives from counties that were heavily populated by peace church people said, well, there's no use. We charge them anything because they're not going to serve anyways. Right. And eventually they settle on the same fee that the federal government was going to use.

And that was dollar 300. Then it went to the state senate. The state senate was kicking it around, and they never did do anything with it. And eventually it became a moot point because, as you mentioned, in March of 1863, then the federal government took over drafting, and it was no longer question. So essentially, the objectors got off without paying anything just because they filed those depositions in the fall of 1862.

Okay. And did they have to provide any proof or evidence that they had these conscientious scruples? I mean, did they need an affidavit or, you know, a note from their minister or anything? Not that I've been able to find, I think they pretty much took the person at their word and at Elizabethown College in their archives, there's a very interesting letter from a brether and leader to a lawyer, and he's saying, well, the question came up, if a person is not a member of a peace church, could he still claim having conscientious scruples? And the attorney said, well, as far as I read the constitution, it doesn't say you have to be a member of any church.

Right. Right. And so it's quite possible that there were men who had no religious affiliation who claimed conscientious object or status in 1862. Now, all the research I've done has pretty much put them all within the historic peace churches. I did a study of the objectors in Bedford County, Pennsylvania, and they all came from either Brethren or Quaker backgrounds.

All right, so that's good to know, though. Don't assume that if a person filed one of these objections, that that meant. They'Re a member of a church that's only under 1862. I'll tell you a little different story in 1860 for the later drafts. O do you want to launch into that story now or.

Sure, sure. Yeah, yeah. So in 1863, as you mentioned, march, the federal government, the Congress, passed what was known as a conscription act. And the Conscription act had no a provision for the direct exemption of COnsc. Contentious objectors.

There were two ways that they could escape service. One was to either pay a commutation fee or provide a substitute. Now, this was not seen favorably by most of the peace churches because they saw providing a substitute the same as sending somebody in your place. And the commutation fee was a little better accepted because they said, well, that's like rendering taxes unto Caesar. So you paid uno, Caesar, what a Caesar is unto God.

What is God s. However, the more strict quakers would refuse to pay the fee or to provide a substitute. The brethren, the midnights, tended to be more willing to pay the commutation fee. There are cases where they also provided, some of them provided substitutes. And there's a story, I think it's, I want to say, the brethren in Christ.

I'm not forget which noination either. Brethren in Christ, I don't think it's menite. Might be a mennite, but there's a story that a peace church man provided a substitute for the war, and he felt so bad about that. After the war, he kept that man's uniform hanging in his attic to remind him that this man served in his place. So, you know, there was a lot of angst about what they should do.

However, I want to emphasize that the primary way that people who were opposed to military service were exempted under the federal drafts was that they were declared physically unfit for duty, unfit for service. So even before they provide a substitute or paid the commutation feea, they might have been determined to be physically unfit. So, for instance, my own ancestor, Adam Stair, in 1865, was drafted, and he was exempted for feebleness of constitution. And he did die in 1866. So I think he was probably in pretty bad shape, and he was only 44 when he died.

So pro. And I think the 1860 census, if I remember correctly, has a tenant farmer living on his property. I assuming he probably had somebody else farming for him. His brother, David Stair, was exempted either in 64 or 65 for loss of teeth in his upper jaw. And you could be exempted if you didn't have teeth, because you couldn't bite the end off of a cartridge.

Right. And in my research, this is kind of gross, but in my research, I found instances where men were either themselves or going to dentis and having their teeth pulled so they wouldn't have to be subject to the draft. So that's in March of 1863, the first conscription act. Well, as this proceeded, they determined that too many men were providing. We're paying the commutation fee.

And so in February of 1864, Congress passed an amendment which greatly restricted paying the commutation fee to specific, very specific cases, and primarily only to conscientious objectors or those having conscientious scruples. And under that act, the people having conscientious scruples had to provide documentation. So that's when you start seeing a documentation required that they were hold the principles themselves. They had to be a member of a church that had peace principles, and they had to provide evidence that they were consistent in their beliefs. It wasn't just something that just happened, but that was still not good enough for the draft.

So in July of 1864, they limited commutation only to contracted objectors, and, well, I just wa wantna throw something in here. The February 1864 amendment often was called the Stevens amendment because Thaddeus Stevens, who represented Lancaster county, of course, he's representing a lot of historic peace church people. Thaddy Stevens was one of the primary movers to keep the commutation fee for those having consciousious scruples as part of the draft process. So after July of 1864, most men who paid the commutation fee had content of scruples. However, because of the way the draft process worked.

There were still people, men who were paying the commutation fee who for other reasons that they're kind of finishing out their cases on. And I think I provide you with a picture of one of the registers that shows non combatants. So if you see the name, if you see the word noncobatant in the draft registers, that's an indication that the person was paying the commutation fee because they were a consientious subjector. So this 1862 enrollment book, this is a state record, then? Well, the Franklin county one has an interesting history.

Oh, okay. Yes. Each county was keeping its own enrollment books. So, for instance, York county, those are the ones that our genealogical society is transcribing. Lancaster county history has.

Lancasterhistory.org has the Lancaster county books. So I think Bucks county historic site has their county books. The Franklin county books somehow ended up in private possession. And in the 18 hundreds, some lady donated them to the National Archives. Oh, and so the Franklin county books are down at the National Archives.

Oay. And I had them. And you can put this on your podcast. I had. I paid to have the Franklin county books digitized for my own purposes.

And a year or two later, the national archives took the images I paid for and put them on their website. So everybody has access to them now. So will everybody please thank me for doing that? Please clap. Although, I'm just kidding.

But I did provide copies of the digital images because the National Archives has no copyright restrictions. So I provided copies of those digital images to the Franklin County Historical Society. Oh, I think the young center over Elizabethtown College, young Center for Annab aboutapus and Test Studies. So I was trying to make them more available because I don't think people in Franklin county knew about them. And this is a great resource.

One of the things we found about using the books here in your county is if you compare these books against the 1860 census, you can find out where men may have moved. And some of the books here in York county have very specific locations. So it'll say that this man lived on so and so, his s farm, or he lived at certain crossroads. So you can take the 1860 census, compare it with these books, and get a much better idea of what's going on with your particular ancestor. Yeah, that's great.

That's great. Yeah. Because knowing that they live on so and so's property, it means they could be a tenant or working for them as sheer labor and some other capacity. And that's always. You can't tell that from the census records at all.

What's going on. Okay, so those county books, enrollment books are at check. The county historical society. Yes. Or.

Okay, good, because I haven't seen that for Montgomery county, which is the one I'm trying to track down. I think years ago I was in touch with a lady at the Montgomery County. A historical society. Yes. Name?

Her last name was Meyer, I believe. Are Myers. Okay. And I think they were at that time in an off site county facility. And I never made arrangements to go see them because at that time I knew what they were and thought, well, they're not going to really give me a lot more knowledge about individs now.

I'd like to see them because I'like to compare them to other counties, but I haven't made arrangements to do that. But I think Montawmery county does have there somewhere in storage. All right. I have a new quest to undertake. If you find them, let me know.

For my ancestor, who was 21 years old in 1862 and did not serve, you made a reference to in terms of physical disability and people that got out of service that way. And those records, please correct me if I'm wrong, would be the provost Marshall records record group 110 at the national archives. That list out who by the provost marshall. So this is the federal draft board, essentially that segment listing out men who. Let.

Let me go into a little detail about that. Yeah, yeah. First of all, you got to keep the 1862 drafts separate from the 1863 and subsequent drafts because 1862, I was referred to as est state draft. And then 1863, you get the federal draft under the Conscription act. Under the Conscription act, the country was divided into draft districts which coincided with the congressional districts.

And so the records for the federal draft are broken down by draft district. For Pennsylvania, all the draft district records are at the National Archives branch in Philadelphia. I want to put a plug in for those people down there. Every time I've been down there, they have been fantastic to work with. Wonderful people, always helpful.

It was great doing research down there.

Any you can get from them a complete listing of all of the records that they have for the draft that were sent to the mid Atlantic or to the Philadelphia branch. And you can organize that by draft district, which is what I did. I think they sent me a spreadsheet, or maybe it was a. I got. A spreadsheet from them.

I did the 6th and the 19th congressional district. I was doing two different ancestral lines. So, yes, it's an immense spreadsheet, if I remember. And they have an older finding aid, which I got before everything was digitized. That's also very good too.

It was the preliminary guide to record Group 110. And there's a section for Pennsylvania. It's broken down by the Pennsylvania so large it had divisional offices. A western division it was, was headquartered in Harrisburg and eastern division headquartered in Philadelphia. And then it's underneath that.

It's broken down by each draft district. And that lists all the records for each or all the district. Records on each draft district can get the same thing from their spreadsheet as well. But the reason I want to go into all that detail is that if you're looking for an individual, what you need to do is identify their draft district and go to the National Archives and pull out any book that says medical register, descriptive register, trying to think of what the other ones are. Generally the registers are the best source.

And then unfortunately some of them are chronological. So you have to. I would ignore the date. I realize you may have to look for a whole register, but you may not know when your ancestor was drafted. So that's what I did for my star ancestors.

I went through all the books for the 16th district, which covered Bedford county. And I did too. I mean, you're just paging through page after page. And I took images of every page so I could go back and look at them a second time, you know, when I got home. And then you'll find information about individuals in these various registers.

And it won'all be in one register. So there might have been a register when they compiled a list of names. So people were going to be drafted. There might be another register called a medical register. When they're examining the people, see if they're physically fit.

So I would advise you to look at every register for that draft district. If there are any special notations about the person, then you want to get into the other records of the district. And I have found great information, not just the district level, but at the ##ision level and also at the federal level. But usually when you get above, outside of Pennsylvania, when it goes down to Washington, a lot of times it's just copies of what they have in the state and local level. So you don't necessarily have to go to Washington.

It's a lot more difficult to do research in Washington than is down in Philadelphia. I would advise going to Philadelphia first, exhausting everything they have. And don't go to Washington unless your ancestor was involved in some very unusual case that was referred all the way up to the provost Marshall in Washington. And then for each draft district, there are correspondence files. Now, a lot of them are just administrative routine stuff.

You know, this is how many men we had drafted, how many men were exempt and so forth. But again, if your ancestor, something unusual happen to their ancestor, you might find something there. For example, my ancestor, Adam Stair, had a brother, Daniel Stair, who ended up paying the commutation fee twice. Towards the end of the war, the war department decided that you only had to pay the commutation fee once, and if you paid it twice, you could get the second payment refunded. So Daniel Stair approached his local provost marshal and with the assistance of his brotherren minister and filed a request to have the second commutation fee refunded to him.

And there's a nice little exchange of letters between the provost Marshall. I don't know if Daniel himself actually wre any letters. I think his minister wrote one of them. And the people in Washington talking about, is he eligible for it? Yes, he is.

He's going to get this money back. And so that's something I found in the correspondence files'at the national archives. In some cases, they also have letter registers where they transcribed abstracts of the letters into registers. If you want to go through things more quickly, you might want to look through the letter registers first, although they don't always give you all the details that are in the letter. Another thing I will say about doing research, particularly to national archives, is pay attention to every notation that's on anything, because every notation refers to something else.

And I'm slowly learning what all these notations mean. And a lot of times they're referring you to other records. And if you know how to interpret their abbreviations, you can find where this, where you can follow the paper trail through the bureaucracy. Ok. And you'll be writing a book about this, correct?

I will not be writing a book. Al, if you're very interested in this topic, I did a presentation for the south central Pennsylvania Genealogical Society on using Pennsylvania civil war draft records. O okay. You go to YouTube and look at that presentation. I go through how to use the records, what's where and what to look for oay.

So that that might be a value. I proably should, maybe I should some day write an article about it, but. I think you should when it comes down to following the paper trail based on those notations. Those are the kind of things that. Well, I think the archivists there will tell you.

Oh, okay. When I had questions, I'd ask archivists and they'd say, well, this point'this and then, or I'd read something and it would point to something else. And so because the civil war is a popular topic over the years, I've had a lot of success in talking to the archivists at the National Archives'interested, in the civil war, and they give you a lot of good information. Okay, good. And I'll link people to that preliminary finding aid for the provost Marshall collection.

It was written in the 1960s. Does not make it any less useful to use. It's actually more useful to use than the National Archives catalog because it is just the summary of the records that you want and it has a short description of what's in each kind of archival box or journal. They have everything boxed up very nicely and you can navigate yourself through it because the spreadsheets immense, I want to say it was like eight pages long or maybe 15 or something. I only asked for the portion related.

Depends. I trying to remember. Yeah, whole thing. I don't know. It took me a couple hours to weed through it because they changed the codes what was in the preliminary archive versus what they coded it now.

So I had to translate things. Well, I'll tell you one thing I did is I developed a spreadsheet for myself where I put previous reference and the current reference and then the title of the series and some other notations I keep for my personal was this helpful or not? Or what's special about this? And I've found that very useful when I go to the National Archives because I can take their old preliminary guide, which sometimes makes more sense to me than some of the things they have now, and then find their current number. And it's very easy if you have their current number to find it on their, their online finding a because you just plug the note instead of putting a title rightthing I put in that number and it takes me right to that thing on's true website, which makes it a lot easier.

And so s my personal spreadsheet has helped me in that respect. Yeahahah, that's a great idea to make up your own finding aid of a sort, because you're researching when you're researching too. I'm assuming you're researching a specific congressional district, right? Yeah, and specific people. So one note and check me if I'm wrong that when you mention the letters being sent amongst the federal government workers, we'll just call them federal government workers.

Those are indexed by the areas where they're sending them and the departments and the workers themselves. You're not going to find an index with your ancestor's name on it within the letter. Correct. If you're looking for one individual, probably the easiest place to start, unless you have a date, is to go to letter register. Look, just go into the index, the letter register, and find the name.

Go to that entry, see what tells you about the letter. And then if you think the letter is going to be helpful, have the letter itself pulled. Now, as far as I know, most of the correspondence files at any level are arranged chronologically, although I think some of them, it might have been at the top office level. They used some crazy system where it broken down by letter of the Alphabet. But if you have the data, if you know that you, you get into, say, a descriptive register and it says something unusual that might say c letter of dates, such and such, well, you can just go right to the correspondence file and look for the letter of that date and you should be able to find it fairly easily.

Okay. All right, so I stand correct it. So our ancestors that were researching who were draftees or not and written about by the federal government, their names are in these draft reg letter, I'm sorry, are in these letter registers, general name. Generally they indexed every name in a letter and letter register. And it gets frustrating.

If you're looking for, or say an officer who's signing off on stuff, he might have signed off on 100 letters and so, and you know, so you go to the index and it says Colnel so and so and you have 100 pages to look at to see if you can find the letter a specific thing that you're looking for. Right. If you have a it'they're, better to use if you have uncommon name now, like their name stairs, not that common. So that's pretty easy to do. But if you have a name like Fisher.

Right, or Myers or you may be looking at a lot of pages till you find something that's useful. Yeah. The other hand is serendipity. You mightounter, you might go to the page and find something you just totally didn't expect, which was how I found those things about men pulling their teeth to avoid service. So.

Yeah, and that's one of those stories that you hear, but you wonder if you hear it, like, is that just something that people made up or whatever? And then when you see the actual evidence in a letter of the time, you're like, no, that was a real thing. And just to reference something that you mentioned when we were talking about the revolutionary war in bureaucracy, this is really the beginning of the federal government making this bureaucratic management of the war. This collection of letters is immense. Like, I think the size of it is like, isn't it like eight football fields long or something?

Like, I think it's like hundreds of feet of. Well, it depends on what level you're talking about. Now, if you're dealing at the district level, there may only be a box or two, maybe three boxes. When you get up to the level of the provost Marshall general's office, I'm trying to remember. I think there's, you know, maybe several dozen boxes.

Yeah, I mean, there's a lot of correspondence going on, like, this entire time. I mean, they're recording everything. They're making registers. They're making, I mean, there's a lot of paperwork. And one other thing I should mention is don't overlook telegraphs.

They were using the telegraph quite a bit, and sometimes they file the telegraph messages separately from the correspondence. So I was always checking telegraph messages as well. And again, it varies from place to place and level to level. But for the individual, the average person researching their family history, I would say you're probably going to find most of what you want to find at the National Archives branch in Philadelphia for the federal draft, for the state draft, youre going to find most of what you want at the state Pennsylvania State archives or at the county Historical Society. You really dont have to go to Washington unless there'something, like I said, something turns up that a special case.

O all right, now, did I take us too far afield? What you wanted to talk about with conscientious objectors? Because I find that provost Marshall collection fascinating. Of course, they were writing about the people that they're trying to draft and the draft ofaders, and they sell as draft ofaders, and there's a lot of car because they were desperate for men to fight in this war. I mean, they really were.

It was always in my mind of man, a battle to the last man standing who could provide enough men to win this thing for people that are, this is brand new to them, and they're thinking to themselves, how would I even know if this applied to my ancestor? What kind of clues would somebody be looking for in the records that they already have, that their ancestor might be a conscientious objector? Because this is involved research. You're talking like, none of this is online, that you're going to type in a search box and have an answer pop up for you. This is archival research.

It's not hard to do. The staff is very friendly, as you mentioned it'but it's an adventure, and we don't want to send people on adventures. If they're not prepared. So let's get them back and give them some clues to look for before they start this adventure. Well, first of all, if there's no draft, there's no conscientious objection.

So you're dealing with a draft situation. Depending on the time period, the draft age generally was 18 to 45. So if your ancestor is not at least 18 in 1862, and he's older than 45 in 1862, he's not going to be in these records. Should even be. More importantly, he has to be male.

Were as far, there were no women who were drafted. Now, there were women who served in the army, but there were no women. The women were not subject to the draft by legislation anyways. So it's a male between the ages of 18 and 45. The most likely other clue that he might have been a conscientious subjector is that he was a member of a peace church.

And I talked about the peace churches earlier. Because most of these groups are small, they tend to have more books that have people's names in them, written about them. So if you know, you think your ancestor might have been a member of the Church of the Brethren in Montgomery county, you pull the history of the church for that area. And if it's a brotherren family, it's probably going to be a mentioned in there.

The Mennonites have a lot of good books. The Quakers do too. So you want Toa look in books about that denomination to see what they might say about your family. But if you verify that the person was a member of peace church during the civil war, eligible for the draft, then you could begin to think, and you don't have any evidence of service in the military. Now I do want to mention's something that most people forget, particularly among the Brethren and the Mennonites.

You did not become a church member until you were generally t, until you were an adult. So you were baptized, and then you became a church member. Many young men from these families went into the military because they had not yet joined the church when the war started. And so you will find particularly brethren and men like families who have people serving in the Civil War because their sons hadn't joined the church yet. And under the 1864 draft amendment, you had to be a member of a peace church.

So you couldn't just say, I had peace principles. You had to have to be a member. And they had to provide an affidavit from that congregation saying, yeah, you're part of, and I have cop. I don't think I sent a copy of that to you, but I have copies of some of those documents now for the 1862 draft. We're very fortunate because the state atts in general, or when the federal government took over the driraft, I forget who did.

I always say the state attn general's office did prepare to register of all those names of men who filed depositions in 1862. That register was then turned over to the federal government, ended up in national archives. And years ago, I was involved in a project with the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania to transcribe the names from that register, put them into a database, and that database is now available free of charge on the website of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania. So if you want to see if your ancestor was an objector in 1862, you can just go to that database. That's a quick way to go and check che to see if possibly the name shows up.

However, there were men who were refused military service whose names do not appear in there, but it's certainly a good place to start. Occasionally you'll find in the newspapers lists of names of people who were seeking exemption as who having conscientious scruples, primarily because the newspapers wanted to point out that these people were sure their duty. So you might want to also, if you have, you go somewhere they newspapers.com and do a search on your ancestors's name from 1860. Well, I would limit it from, say, August of 1862 to April of 1865. Then you won't get so many hits and you can see if your ancestor's name showed up.

Interestingly enough, Adam stairs name shows up in the Bedford county paper as it being subject to the draft in 1865. Now, it doesn't list them as a conscious subjector, but it does show him among the men liable for the draft at that time. I've had a lot of fun with newspapers because newspapers, most newspapers, had a very political point of view. And you can get some pretty interesting comments about both for and against the draft and what they thought of people escaping them. And they called conscious subjectors all kinds of names.

You know, there was s a lot of accusations in Bedford county, for instance, that sharkers and skulkers and slackers were using supposedly consciousness scruples as a means of escaping the draft. But that might have just been their democratic point of view, because that was a democratic paper that was saying that, I don't know, you're probably gonna cut me off soon. I do wantn mention a couple books that I provided you copies of. Just so if people want to know more about how this all worked, the best book on conscientious subjectors in the Civil War is the titles Menonites Amish in the American Civil War by James Layman and Stephen Knl. Although it deals primarily with the Mennonites, what they talk about generally applies to contentious objectors across the spectrum.

And the nice thing that they do is they recognize the difference between 1862 draft and 1863 and subsequent drafts. They also recognize the importance of regional and local differences. And if you have mennonite ancestry, they actually have a list of some mennonite names, I think in the appendixes of that book. I highly recommend that book because it'probably has the best understanding of how the draft impacted the peace churches. Now an older book which can be useful is Edward Wright's conscient subjectors in the Civil War.

It was first published in the 1930s and then it's been reprinted a number of times since then. He deals more with the Quakers. I mean, he does deal with the other peace churches, but he deals more heavily with the Quakers. So if you have Quaker ancestry, his book, you might want to refer to that to understand the draft. The best book is James Geary's we need men.

Now that is an overview of the draft. It's a draft in the north. I shouldn't emphasize that I'm talking primarily in the north here, but his book is excellent in understanding the legislation, how it was carried out and so forth. And he has good charts in there to show you how many men were drafted. He talks a lot about these exemptions and so forth.

It's a good book. However, a better book for understanding how the draft actually worked. If you want to know what it was, a provost Marshall, what was the role of the board of enrollment? What was substitution? What was commutation?

The best book that I've found on that subject is 1 million men by Eugene Murdoch. Now Murdoch wrote several books on the Civil War draft, but 1 million men is a good book to, if you want to understand the role of the various, we're talking about the bureaucracy, the role of various pieces of the bureaucracy. And he uses a lot of pennsylvan examples in his book. So it's good for people who have Pennsylvania ancestry. I found that very useful in trying to understand how the draft actually works.

So what was the draft wheel and how did they use that? And he talks about things like that. So those are the, what I consider the top four books that people should consult. Another if you're going to do research at the National Archives. Another good source is the author is William Iter.

It's a doctoral dissertation. It's conscription. I think it's either civil War conscription in Pennsylvania or conscription in Pennsylvania during a civil, or something like that. I should have sent you a copy of that. But he wrote his dissertation, I think, in the 1940s, so it is sort of outdated.

But the nice thing I like about it is he cites heavily the records of the National Archives. And so if you want to know what particular records that you might want to look at, go to his dissertation, read what he says about the time period that you're interested in or the location, and look at his footnotes in bibliography. And I've found his, his dissertation to be helpful in my research. So those are some of the sources that I would suggest looking at if you want a broader understanding. Otherwise, just do what Denyse and I did and dive into it.

And like she said, the records are just wonderful and fantastic to look at. Yeah, yeah. They're super detailed. It's amazing the level of detail they were undertaking, trying to, you know, account for the men that they were trying to keep track of.

I got distracted when I was researching, you know, as they were trying to track down deserters and developing descriptions of them. And then the bounties that you. But that's a whole nother conversation. We won't get into that. That's another whole rabbit trail to go down.

But Jonathan, I'm not going to cut you off, but I will ask you so we can wind up this conversation for folks. What else do you want us to know about Consc. Object. Conscientious objectors in the civil war? Before we sign off for the podcast.

Well, several things I would mention briefly. First of all, this is a very overlooked aspect of the Civil War. Even though I mentioned some books, very little has been written about it, and even less has been done in the genealogical community about documenting these. Probably some of the work that I've done has been the most detailed. So if you have Bedford county ancestors, I'did an article in the Bedford County Historokicide newsletter for them's been most of my focus in writing, but I'd be glad to help anybody who thinks they have an ancestor in Pennsylvania was a content subjector during the Civil War.

So that's one thing I want to mention. The other thing I want to mention is this. I'll call it a problem. The problem of the contract subjectors was a very small issue compared to everything else related to the Civil War, and that was concerning the draft bureaucracy, because obviously, if these men are refusing military service, they're not going to be the ones that are going to be violently opposing the draft. And when you get in the draft records, there's much more information about people who are violently opposing the draft or threatening the lives of provost marshals or threatening aive enrolling people.

So I've had to dig through a lot of stuff to find a few really choice tidbits. Don't expect this to be like, I mean, every now and then you hit a nice little load like I did on Daniel Stair, but it's not going to be a super big gold mine that you're going to find. You're going to find little details here and there. I want to emphasize that in closing, I want to emphasize again and again and again and again, everything is relative and local. So don't assume that what applies to Pennsylvania will apply to another state.

And don't assume what you find in one county applies another county. For instance, the provost marshall of the 16th district, George Easter, kept very good record records, produced mounds of good stuff, and that covered where my ancestors lived in Bedford county. The provost Marshall in Lancaster County, I think they had three over the course of the war, one of them being Thaddeyus Stevens nephew. Thaddey Stevens Junior, kept very poor records. And the records there are not nearly as rich as they are for the 16th district.

And we would like to know a lot more about what was going on in Lancaster county, because that's where the concentration of Peace church people, one of the concentras. Anyways, anyway, so it just goes to show you, each county in Pensylvania draft district in Pennsylvania is different. And keep that in mind as you do your research. Oh, I had no idea. That might be a way to gum up the draft as you do poor paperwork.

They're unable to. Well, actually, I. I think it was a letter or might have been a telegram or something in Lancaster county, where I don't know if it was when Thaddey Stevens Junior took over the office or the guy before him said that when he went to the office, he couldn't find some of the records and some of the records hadn't been kept, and things were a mess. And I thought, well, if it was a mess back then, we're not going to much luck today. That's funny.

All right, Jonathan, thank you so much for sharing your passion, conscientious subjectors with us, because it is. It's an unexamined part of the civil war. That time period is way more complicated, I think, than we ever give a credit for. Despite it having more books published every year than almost any other history topic in the United States. This topic of men and their attitudes towards fighting, the choice to fight or to participate in everything really isn't covered a whole lot.

And I know as genealogists it is something we are really interested in because we want to know our ancestors as people, not just names. And so thank you for giving us a window into that. I really, really appreciate it. And just thank you for sharing your wealth of experience with us's very helpful. Thank you for this opportunity.

You know, I always like to talk about the subject, so. All right. And as you have a new discovery or you do more research, let me know and we'll come back and do a follow up. Yeah. Because I'm going to be continuing to research this, too.

We don't have an anniversary of the civil war coming up, a significant one, anytime soon, but that doesn't mean we don't research the topic anyway. Right. All right.

Thank you. You're welcome.

Bye now.

© 2019–2024 PA Ancestors L.L.C. and Denys Allen. All Rights Reserved.