Vital Records Research: Getting Started in Pennsylvania Research

An overview of how Pennsylvania records are organized and a suggested research approach.

For many family historians, their first hint they have Pennsylvania ancestors is a notation on the census or a death certificate of “Birthplace: Penna.”

Their next step is searching on one of the major genealogy websites for birth records. However, it soon becomes clear that research in the Keystone state is quite confounding! There are not as many birth, marriage, and death records as family historians assume there would be. Many of the historical vital records remain unindexed, and therefore, are not returned through search on genealogy websites. This book will cover in its chapters exactly where to find vital records and how to search for them.

But first, knowing how Pennsylvania is organized and having a approach to research in the state can help you get started, or re-started, on solid footing.

- Pennsylvania began in 1681 when William Penn received the charter for the land from England. Its first laws were issued in 1682.

- There are sixty-seven counties in the state now, including the City of Philadelphia which was founded in 1854 from the boundaries of Philadelphia County. Some today say there are 66 counties plus the City of Philadelphia. The important part to remember is that both land and counties were added from 1682 to 1878. County boundary line changes are not covered in this book. See Appendix E:Additional Resources for Research for help with county boundary changes.

- Migration was difficult in a straight east–west direction across the state due to the Appalachian Mountains. There are also few rivers navigable by boat, and those run north–south. People migrating from the Philadelphia area typically went south to Maryland and Virginia, then north to get to the Pittsburgh area. Keep this in mind when tracing the movements of ancestors.

- County records are essential to vital records research, yet there is no central collection in the state of all county records. Pennsylvania's adjoining states of Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey have moved most of their county records to their state archives. Pennsylvania has not done so due to the volume of county records. Many county records have been microfilmed over the years by the Utah Genealogical Association (now FamilySearch) but no county has a complete collection microfilmed and available through search online. Each chapter in the book provides checklists of how to search for each record type both online and offline. Artificial Intelligence (AI) holds the promise of indexing all records on microfilm in the near future, but until that happens, the research approach in this book works.

- Pennsylvania had, and continues to have, distinct regional differences: east to west, north to south, center to borders, and even county to county. Assuming people in one location kept their records in the exact same way as people in another location can trip up researchers. Record-keeping practices are similar across each record type, but there are differences by location and ethnicity, particularly the farther back one goes.

- Pennsylvania ethnic diversity is astounding. AncestryDNA counts eighty distinct genetic communities across the state. To use your autosomal DNA results with your vital records research, see Chapter 2: Using DNA Results in Vital Records Research. If you have not done a DNA test through Ancestry, you do not need it. In most cases you can complete your research successfully without it.

Now that you know this history and structure of Pennsylvania and its records, let's cover an approach for genealogical research that combines the power of genealogical websites and methods for analysis.

Suggested Research Approach

As was mentioned, there is little success in using the main search box on any genealogy website to find all the records you need. The approach I am suggesting here combines what is available online through search with some additional analysis on the researcher's part to find what is needed. Here are my four steps for successful genealogical research in Pennsylvania:

- Begin at the end of a person's life and work backwards

- Create your own databases of records

- Collect vital records on every family member

- Write about what you find as you research

Combine these four steps with the specific checklists at the end of each chapter for maximum results.

Begin at the end of a person's life and work backwards

Every biography and memoir starts with a person’s birth, moves through to the events of his or her life, and ends with his or her death.

It is tempting to research in this order of birth to death, but it can create frustration and confusion. For most of our ancestors, state law required more records be created at the time of their death than when they were born. By starting at the end of a person's life where we have more records, we can gather the details that will help us locate the correct birth record.

Collect every record an ancestor made where he or she died. This includes their entire estate filing (also called probate records), property (deed) records, cemetery information, obituary, and anything related to their religious practices. Most of these records are county records and were filed at the county courthouse where that ancestor lived. County newspapers are not all online, so check with the local genealogical society on where to find more newspapers. In most counties there are eight to twenty newspapers available on microfilm.

Once these records are collected combine them with the census records you have and assemble the details into a timeline of that ancestor's life. You may want to also use maps to identify exact locations and family nearby. By the end of this assembly, you should have enough information to be able to pluck your ancestor out of a group of similarly named people based on what you know. (And chances are you will encounter many similarly named people while researching in Pennsylvania!)

Create your own databases of records

When you create your own database, you can ensure that you have a thorough listing of every person with a name similar to your ancestor, and an exact location where each person lives. Plus you will have a listing of every spelling variation of that surname.

First, let's cover surname spellings, then we will create a database.

Two factors confound genealogists researching anywhere: the number of people with similar names and the number of spelling variations for surnames. In the present day, we expect people to have one, and only one, spelling of their name. But for any time prior to about 1930, the spelling of a surname could vary from slightly to significantly. Genealogy websites often assist in showing additional records with similar sounding surnames or abbreviated spellings of given names. What can be helpful is to make your own list of the various ways you have found a surname spelled or use existing resources to intentionally misspell names to ensure no name is missed. See Appendix D: Additional Resources for Research for help with name variations.

Here’s an example of the many ways a German ancestor of mine had his surname spelled on documents:

- “Streibach,” 1860 U.S. census

- “Strwick,” 1870 U.S. census

- “Streibig,” 1880 U.S. census

- “Striebig,” Philadelphia Death Certificate, 1887

- “Streibig,” Union Army Pension File Index Cards

- “Streivish” and “Strinwich,” Compiled Military Service Record for Union Army

Those are the variations for one man! His siblings and parents had even more spelling variations of their shared surname. It appears that my German-speaking family could not spell in English and simply said their name to clerks, who spelled what they heard. A common situation for many non-English speaking immigrants.

Additional spellings of "Streibig" were found as I collected records on all the Streibig's who lived in the area, Most of them were related to each other, so I simply added them to my family tree. I then copied and pasted each spelling I found into the top of my research log so I had a list of what to search in each new record collection.

Now we will cover how to create a database of records from genealogy websites.

Why create your own database of records? Having your own database allows you to methodically go through each record for your ancestor and make notes of your results. For example, in the censuses prior to 1850 only heads of households were listed by name, and no one else in the family. By creating your own database of a pre-1850 census, you can target your focus on households of the surname you need by specific locations. Each household can be checked for people that match the age of your ancestors, and those that do not can be eliminated. This process results in a small list of possible families for further research, rather than trying to tackle the entire state (or country) at once.

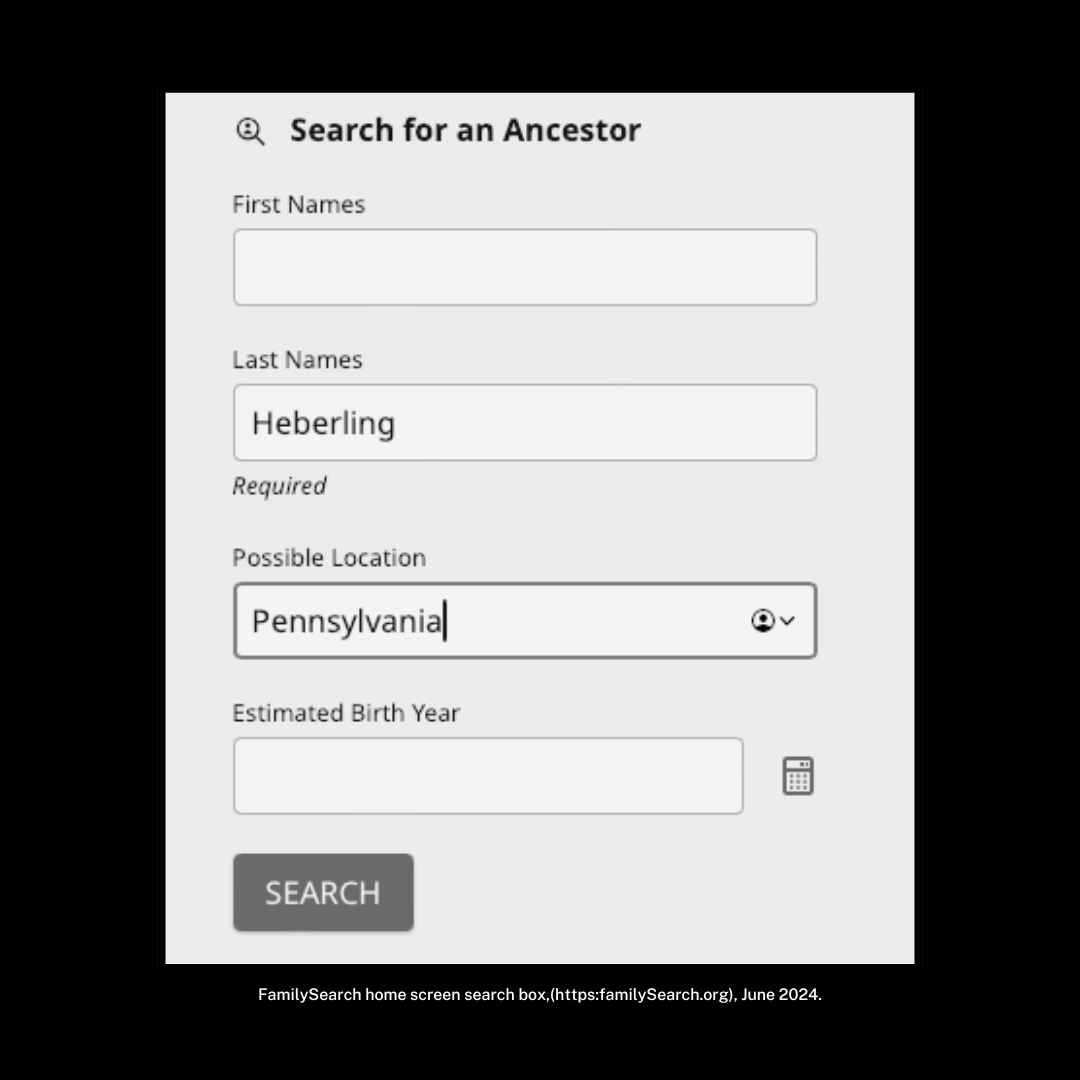

The two tools you need to create your own database are a spreadsheet program (Excel, Numbers, GoogleSheets) and a free account on FamilySearch.

In the example below, I will show how I built a database of all the Heberling's in the 1830 census in Pennsylvania. My research question is to find the parents of Joseph Heberling born around 1814 in Pennsylvania. I know from census records and the vital records of Joseph's children that he was born in Pennsylvania, but no county. I have used census and tax records to follow Joseph Heberling's life from 1868 back to 1836 in Ferguson Township, Centre County. There are no other Heberling families in Ferguson Township, so my goal is to find other Heberling households in Pennsylvania in 1830 where Joseph could have been born. To ensure I examine each Heberling household, I am going to create a database of 1830 census records.

1.On a desktop or laptop computer go to FamilySearch.com and log in. Using the main search box, type in your ancestor’s surname in the surname field, and “Pennsylvania, X” in the location field. X is the county you wish to search if you have a county. If not, just type Pennsylvania for the location. No need to enter a birth year or death year and click Search.

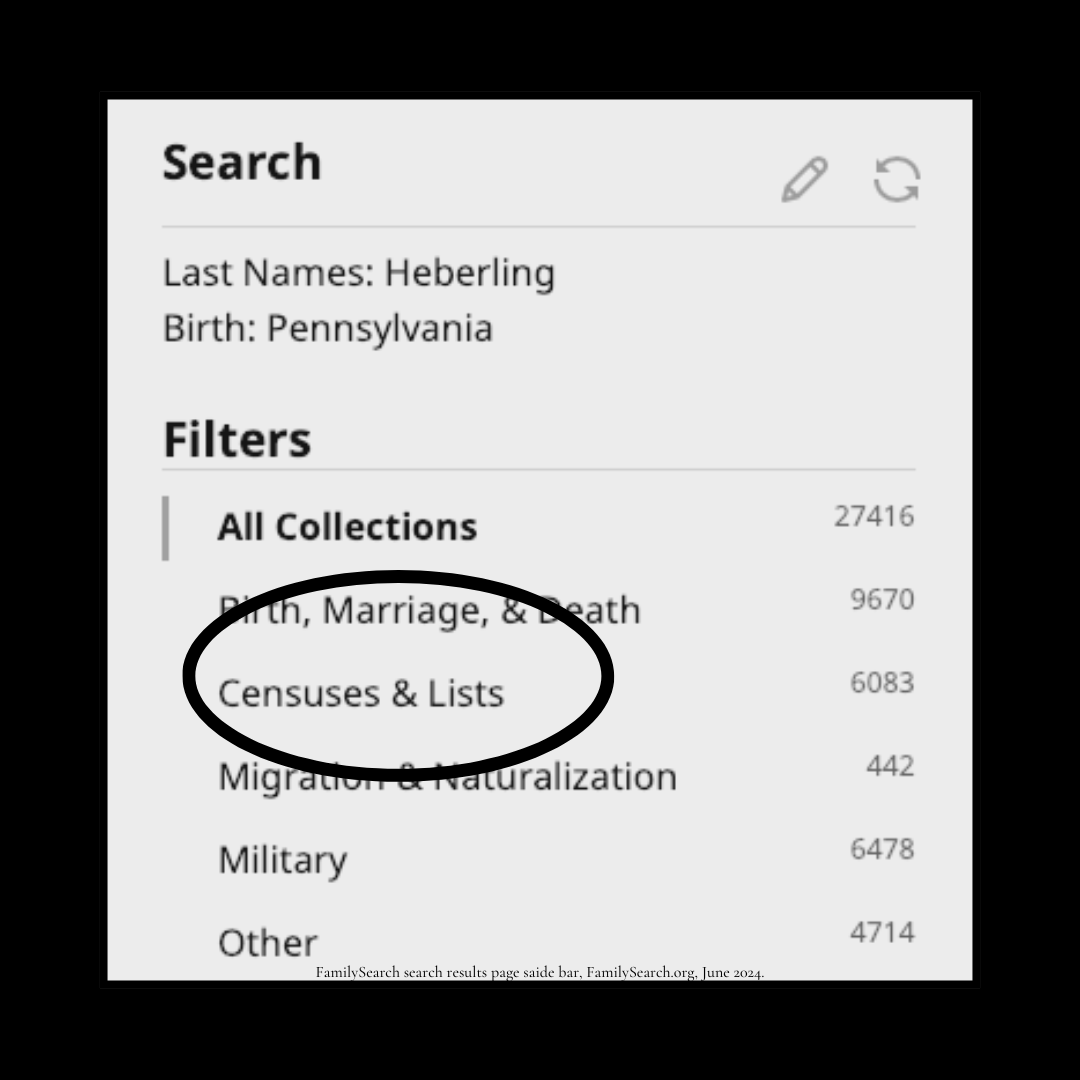

2. You will get thousands of results returned. Ignore them.

3. Look at the “Collections” in the side column. Choose the option for censuses.

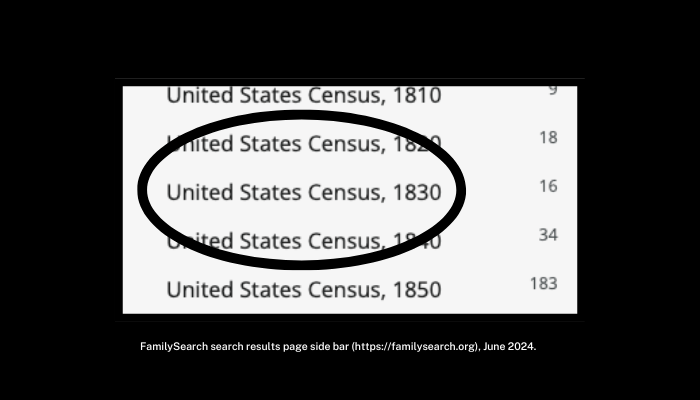

4. Scroll through the list until you see a census collection for the year you want. For my Heberling example, I am using "United States Census, 1830". Click on this record collection title.

5. What you now have in the search screen is very focused list of all the heads of households with your ancestor’s surname who lived in Pennsylvania at the time of that census. In this example with Heberling's in Pennsylvania in 1830, I have 16 households. A very focused and targeted search!

Note: FamilySearch is continually changing their website design so the images of the website shown here may not match the current website. However the steps involved of going from a broad search to a narrow one are the same.

Before June 2024 there was the ability to download these search results along with the attached record image as a spreadsheet file. Currently no download option exists. You can either copy and paste the information for each record into a spreadsheet with links to the image, or you can search for a data scraping app to do this for you. Data scraping is against the terms of service of most websites, so I can not advocate doing this, but it is possible.

Regardless of how you build your spreadsheet, working off a targeted list of households or individuals is superior to using the general search box. You will be able to methodically examine each household against what you know of the family and narrow your search to just those who meet your criteria. Plus by making notes of your search results along the way, your family members will be able to follow your research trail and understand how you reached the results you did.

Lastly, repeat the search and database building for each variation of the surname spelling you have. Usually genealogy websites assist in providing alternative spellings, but as I showed in the Streibig example above, some spellings are so far off the usual spelling variations, that they get missed.

Collect vital records on every family member

Because family members are born and die in different times and places, the types of records each one creates can vary in quality. For example, Philadelphia's Department of Health began keeping death records in 1860. Those records began as listings of each individual in a ledger book. By the mid-1870s it evolved to single forms per person. The city's form evolved again to something similar to state death certificates in 1904. With each change to Philadelphia's death records, more information was collected on the deceased. Your direct line ancestor may not have the information you seek on his or her vital records, but you could find it on a sibling's record.

Each chapter in this book will tell you specifically which vital records exist by year and where to find them. If vital records do not exist for a particular time period, a list of other record suggestions is in Chapter 10: Substitutes for Vital Records.

When collecting vital records, obtain an image of the original form. Do not settle for what comes up in computer search summary page or index listing. It really does matter for family history to have that photocopy image or digital image. Frequently genealogy websites just show parts of the birth, marriage, or death records at first. Click through to view images and download them to your computer. These original record images will have additional details such as doctors, hospitals or institutions, ministers, informants, or burial details. Through out the book when I refer to vital records, it is these original records (or their images) I am referencing.

Write about what you find as you research

Almost everyone skips this step. Most researchers stay stuck in “collecting records” thinking if they just keep searching online, everything will fall into place. What often happens is repeated searches, frustration, and mistakes.

Writing about what you find as you find it (or do not find it) prevents errors, and speeds up research. Writing encourages you to look closely at the records and put them in logical order. Once they are in order, you start noticing gaps between records or repetition in people and places. Connections and patterns previously hidden will be revealed.

Before launching into new research, take some time and make a listing of everything you have found so far. Put it all in a research log writing about the details in each document in one of the columns, or write it out in a Word document. Writing with pen and paper works too! Simply open a document image and write about the details of what there. Carefully read every field, every notation, and even the back of the form, then type it into your research log or Word document.

This step feels tedious and not useful, but most researchers find they make major breakthroughs in their research when they write. Details and patterns emerge as our brain examines the facts we have found so far. We also note what is missing and discover new avenues for research.

Once you have assembled what you have and written about it, it is time to begin your research in vital records.

From the book Pennsylvania Vital Records Research, by Denyse Allen. Print and ebook copies available on Amazon https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DQX915KK

© 2019–2024 PA Ancestors L.L.C. and Denys Allen. All Rights Reserved.